Through our discussions, conferences and events, which bring the action plan to life, we regularly hear from you. Here, we list your frequently asked questions and try to answer them as best we can with the help of the experts supporting the action plan.

What is decolonisation?

Since the end of the Second World War, the term “decolonisation” has referred to the historical process of freeing colonised peoples from the domination of colonial powers.

But the accession of many countries to independence has not put an end to the maintenance of colonial relations in people’s minds and in political, economic and cultural terms. Since then, in the 1990s, researchers have proposed broadening the meaning of the term. The term “decolonisation” is now used to denounce the persistence of this situation and its consequences, particularly for racialised people. Decolonising therefore means wanting to put an end to this domination in order to establish true equality.

The decolonial approach challenges the idea that knowledge can be totally neutral. It also criticises the Europe-centric view of the world and highlights how modernity was built on exploitation and racially based inequality.

Decolonisation is a global process, which does not only concern the political level. It also affects mentalities, public space, education, architecture, the economy, international law, and many other aspects of society.

To go further:

- Towards the decolonisation of public space in the Brussels Capital Region: a framework for reflection and recommendations. Report of the working group, Brussels, Urban.brussels, February 2022 (Report 2022).

- COLIN Philippe and QUIROZ Lissel, Pensées décoloniales (Decolonial Thoughts). Une introduction aux théories critiques d’Amérique latine (An introduction to Latin America’s critical theories), Paris, Zones/La Découverte, 2023.

- CONNELL Raewyn, Décoloniser le savoir (Decolonising Knowledge). Sciences sociales et théorie du Sud (Social Sciences and Theory of the South), translated by HEL GUEDJ Johan Frédérik, Paris, Payot et Rivages, 2024.

- DUFOIX Stéphane, Décolonial (Decolonial), Paris, Anamosa, 2023.

- RUTAZIBWA Olivia Umurerwa, Het einde van de witte wereld (The End of the White World). Een dekoloniaal manifest (A Decolonial Manifesto), Berchem, EPO, 2020.

- THIONG’O Ngugi Wa, Décoloniser l’esprit (Decolonising the Spirit), translated by PRUDHOMME Sylvain, Paris, La Fabrique, 2011.

What is the decolonisation of public space?

Public space refers to all places that are accessible to everyone: streets, squares, parks and the like, but also museums and their collections. It is also a place for political debate and for the democratic circulation of points of view. The past few years, protests and debates there have multiplied.

These discussions are not just about colonial cultural heritage. As a matter of fact, public space is not neutral, and it is the bearer of values and choices inherited from the past.

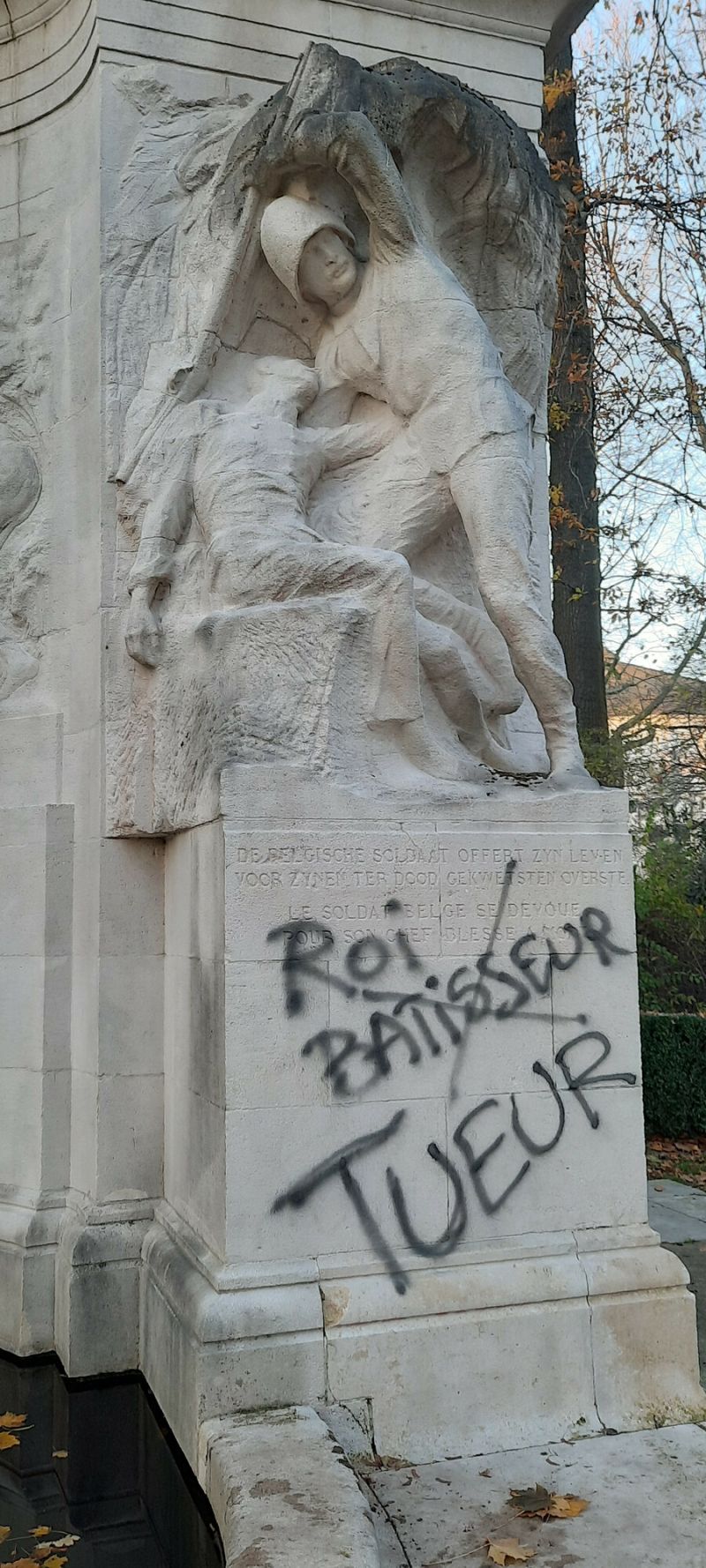

Today, some people are advocating the decolonisation of public space. Contrary to popular belief, decolonisation does not mean erasing all traces of the colonial past. It is about looking at them differently.

The decolonisation of public space involves rethinking colonial memory by combining a revision of the representations, the transmission of knowledge about colonial history and a reflection on their current impact in Belgium and in Africa (Report 2022, p. 218).

To achieve this, we need to identify the colonial traces and document their significance, as well as the events and the people to whom they pay tribute. This process of contextualisation must be accompanied by an open debate with the citizens. A participation process and a space for dialogue, supported by scientific tools, must be set up around each colonial trace. The aim is to co-construct other approaches, for example by installing explanatory panels or art work. It is also important to make room in the public space for the former colonised peoples - the Congolese, Burundians and Rwandans - and their actions and commitments.

To go further:

- Towards the decolonisation of public space in the Brussels Capital Region: a framework for reflection and recommendations. Report of the working group, Brussels, Urban.brussels, February 2022 (Report 2022).

- GODDEERIS Idesbald, “Mapping the Colonial Past in the Public Space. A Comparison between Belgium and the Netherlands”, in BMGN - Low Countries Historical Review, vol. 135, no 1, 2020, p. 70‑94.

- KESTELOOT Chantal, “Décoloniser l’espace public ?” (Decolonising public space?), in Journal of Belgian History, vol. LII, no 4, 2022, p. 125 138.

- PAQUOT Thierry, L’espace public (Public Space), Paris, La Découverte, 2024.

- TRUDDAÏU Julien et al., “Décoloniser l’espace public, un enjeu démocratique” (Decolonising public space, a democratic challenge), in Bruxelles Laïque Echos, no 120, April 2023, p. 20 24.

- VERBEKE Davy, “Verlegde Sisyfus een steen? (Did Sisyfus shift a stone?) Gecontesteerd Belgisch koloniaal erfgoed en de herdenking van de herdenking (2004-2020)” (Contested Belgian colonial heritage and the rethinking of the remembrance), in Brood en Rozen. Tijdschrift voor de geschiedenis van sociale bewegingen, no 3, 2020, p. 50 59.

What is a colonial trace?

The notion of trace is difficult to define. It concerns marks and symbols that are to be found in public space. These traces are the result of choices made in the past, and as such, they continue to influence us. These traces can relate to the world wars, the place of women in society, but also the colonial past.

In this respect, the Brussels public space contains many traces that refer directly or indirectly to the colonial past: monuments, statues, buildings, place names, art works, parks, etc.

In the frame of the action plan, the first aim is to identify, in the Brussels Capital Region, the traces of the Belgian colonisation period during the Independent State of the Congo (1885-1908), Belgian Congo (1908-1960) and Ruanda-Urundi (1919-1962).

Although they were created after the colonisation period, the traces relating to the history of Burundian, Congolese and Rwandan presence in Belgium as well as the recent creation of decolonial traces will also be taken into account.

To go further:

- Towards the decolonisation of public space in the Brussels Capital Region: a framework for reflection and recommendations. Report of the working group, Brussels, Urban.brussels, February 2022 (Report 2022).

- Bruxelles en Mouvements (Brussels in Movement), no 297: Bruxelles, ville congolaise (Brussels, Congolese city), November-December 2018.

- GODDEERIS Idesbald, “Colonial Streets and Statues: Postcolonial Belgium in the Public Space”, in Postcolonial Studies, vol. 18, no 4, 2015, p. 397 409.

- LEWIS Nicholas, Traces et tensions en terrain colonial (Traces and tensions on colonial territory). Bruxelles et la colonisation belge du Congo (Brussels and the Belgian colonisation of the Congo), Paris, Shed Publishing, 2023.

- STANARD Matthew G., The Leopard, the Lion, and the Cock. Colonial Memories and Monuments in Belgium, Leuven, Leuven University Press, 2019.

Do statues reflect history or memories?

Statues and monuments reflect what societies - or at least their leaders - have deemed important enough at some point in their history to be featured in public space.

Therefore, it is not a question of history, but of the memory of choices made or visions shared in the past. It is possible that these choices and concepts no longer match up with today’s values and are therefore open to challenge. This in no way means erasing history, but rather seeing that past and the choices made decades ago in a different light. As a matter of fact, history is defined as the critical and evolving knowledge of the past. It is the result of collective and contradictory research by historians.

In conclusion, modifying, moving or removing monuments or statues in no way means erasing history. On the contrary, it is all about allowing more room for history in public space.

To go further:

- Towards the decolonisation of public space in the Brussels Capital Region: a framework for reflection and recommendations. Report of the working group, Brussels, Urban.brussels, February 2022 (Report 2022).

- GENSBURGER Sarah, “Pourquoi déboulonne-t-on des statues qui n’intéressent (presque) personne ?” (Why topple statues that are of no interest to (almost) anyone?), in The Conversation, 29 June 2020.

- GENSBURGER Sarah et WÜSTENBERG Jenny, Dé-commémoration (De-remembrance). Quand le monde déboulonne des statues et renomme des rues (When the world topples statues and renames streets), Paris, Fayard, 2023.

- KESTELOOT Chantal, “Léopold II et les autres (Leopold II and the others). Des statues controversées dans l’espace public en Belgique (Controversial statues in Belgian public space)”, in Politika, 27 June 2023.

- LALOUETTE Jacqueline, Les statues de la discorde (The statues of discord), Paris, Passés composés, 2021.

- TILLIER Bertrand, La disgrâce des statues (Statues in disgrace). Essai sur les conflits de mémoire, de la Révolution française à Black Lives Matter (Essay about memory conflicts, from the French Revolution to Black Lives Matter)/, Paris, Payot & Rivages, 2022.

Contact us

Do you have a question or a suggestion?

Do you wish to keep us up to date about an event relating to the decolonisation of public space?